Timeline

Scroll down or use the drop down menu to jump to a specific Expedition:

Discovery:

31 July 1901The purpose-built expedition ship Discovery sailed from London with a crew of Royal Navy and Merchant seamen and scientists. Robert Falcon Scott of the Royal Navy led 49 officers and men. The expedition was funded by the Government, the Royal Society, the Royal Geographical Society and support was provided through private donations. Of the officers, Albert Armitage and Dr Reginald Koettlitz had been members of a previous expedition, the Jackson-Harmsworth Arctic Expedition to Franz Josef Land in 1894.

Discovery expedition team leave London

Discovery headed for Cape Adare, exploring the coast and sailing south along the shore of Victoria Land they landed at Cape Crozier. Whilst there, Lt Charles Royds RN and Dr Wilson climbed to 1,350 feet and saw the Great Ice Barrier stretching out in front of them. They travelled along the edge of the barrier to its outer reaches, where they found areas of rock rising 2000 feet above them. Scott named this area King Edward VII Land. Before returning to McMurdo Sound, where they intended to spend the winter on board Discovery, they paused to allow Scott and then Shackleton to undertake the first Antarctic flights in Eva, a tethered hydrogen balloon. They both reached 250m, but the balloon was unable to be used again as it developed a leak.

Reaching Antarctica

A site was found to winter at the southern end of Ross Island and they named this area Hut Point. A large hut was built, but the men's living quarters would still be on board the ship, which was easier to keep warm. Two smaller huts and a thermometer screen were constructed to house the scientific instruments. This meant that the men had to leave the ship with just a candle to light their way, every two hours, to read the thermometer. High winds would often blow out the candle, which was almost impossible to relight without returning to the ship. Life was slightly more comfortable inside Discovery as the lighting was provided by electricity generated by a windmill, until this was destroyed in a storm in May 1902.

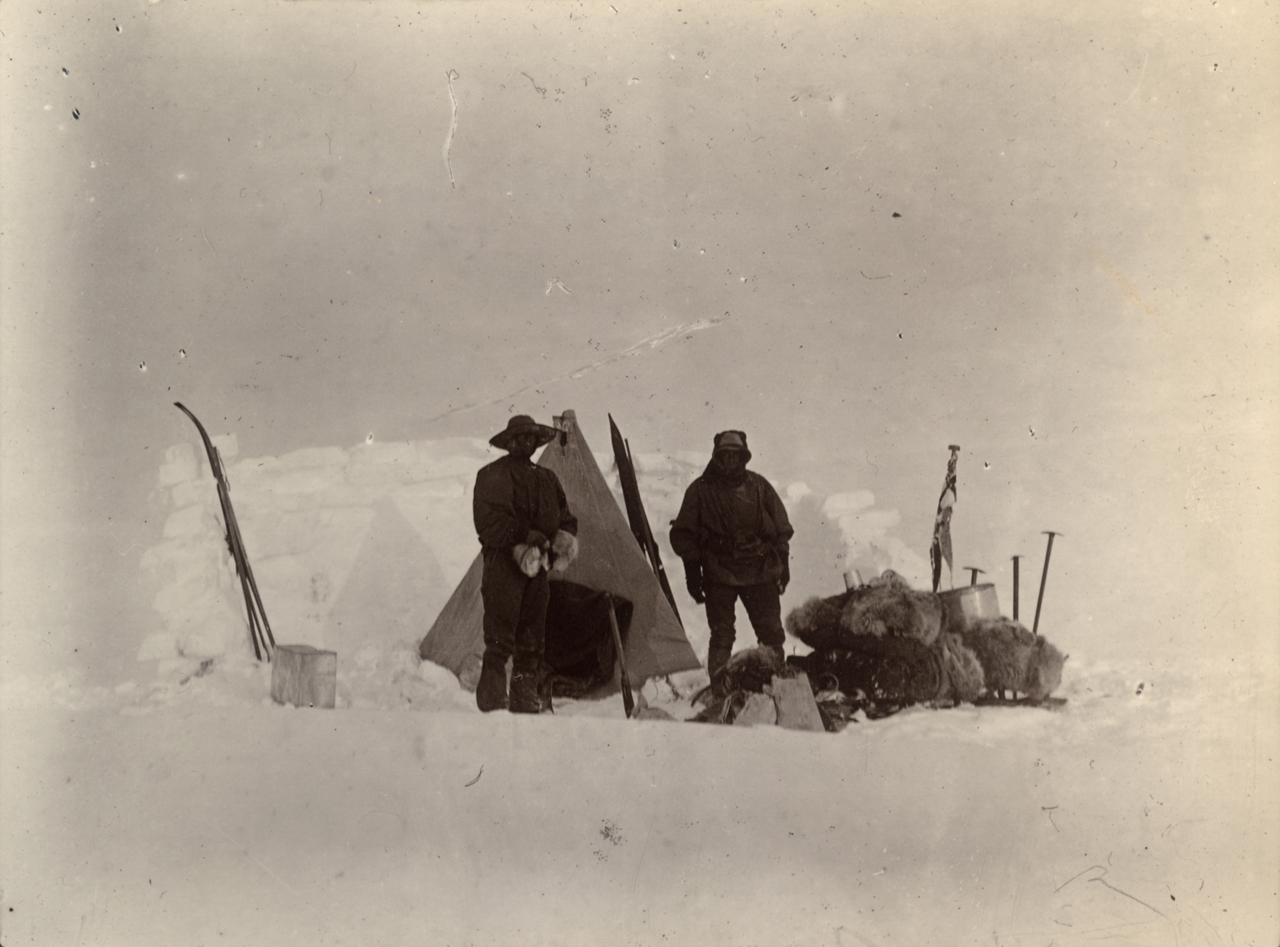

Before the winter set in, short preliminary sledging trips were planned to carry out reconnaissance and to test the equipment. Wilson, Shackleton, and Hartley Ferrar man-hauled their tent and supplies on a sledge to White Island. This journey took longer than they had anticipated, teaching them that distances in the Antarctic are deceptive; they thought they could reach the island within a day and a half's sledging, but it took them two days. They were then hit by a blizzard, delaying them further. This taught them the need to respect the Antarctic environment and to prepare more carefully in case of unexpected delays.

A further sledging trip to lay depots of food and fuel for the spring sledging parties was undertaken before winter set in.

Preparing for winter and learning about their environment

Led by Royds, a small expedition party including three officers and eight men using four sledges set out for the penguin rookery at Cape Crozier to leave a record of the location of their winter quarters in case another ship was sent to search for them. They had taken dogs with them but the soft snow made their progress very slow.

A small group sets off

By the fourth day most of the dogs were lame, slowing their progress. Because of this, Royds reduced his party to himself and two officers (Koettlitz and Reginald Skelton) sending Lt Michael Barne RN and the other men back. The reduced party still found the going very tough; and unable to reach the penguin rookery they too turned back. One of the dogs died on the return journey and the others didn't last the winter.

Returning to the ship

The last of the group safely returned to Discovery, but on their return Royds' reduced party discovered that the party sent back earlier had had a terrible journey. Reaching the summit of Castle Rock the men were caught in a storm. Having managed to pitch their tents but unable to make any warm food, they began to suffer from the effects of frostbite. Spurred on by the thought of being so close to the ship, they struck out for Discovery. This was a serious error and the group became separated. Clarence Hare went missing from the group when he returned to get his boots, whilst PO Edgar Evans RN, Barne, and Arthur Quartley RN found themselves trapped on a snow patch at the edge of a precipice over the sea, unable to go up or down. Meanwhile, the rest of the party continued on, believing they were heading towards the ship to get help. Instead they walked to the edge of a sea-cliff – a warning was shouted, but one of the Able Seamen, George Vince, had a poor grip and slid over the edge of the cliff. Slowly, the rest of the party was able to climb uphill and made it back to the ship to raise the alarm.

The ship's siren was blown, and a search party was sent out to look for the missing members. Sadly, Vince was never found – presumed dead – it is believed he was washed out to sea. Barne, Evans and Quartley were found wandering confused on Castle Rock, very frostbitten, and were brought back to the ship. Two days later Hare, who had been given up as lost, was spotted coming down a hill. He had survived by making himself a shelter of rocks, where he fell asleep and was buried by the snow. When he woke 36 hours later he was able to kick himself free of the snow, miraculously unhurt.

Safe return back to Discovery

On Easter Monday, 31st March, Scott started off on another trip with Armitage, Wilson, Ferrar and eight men with three sledges and nine dogs. They had a very difficult journey with the dogs refusing to work as the temperatures fell. After two days Scott decided they should return to the camp.

Another failed attempt

In April, the sun was seen for the last time for four months. Strong gales made sight difficult, and lines were run between the ship and the huts to prevent the men getting lost when taking measurements. To prevent monotony a winter routine was established with each man having assigned task. To entertain themselves, the men played football, formed a theatre group and learnt to ski and toboggan. Shackleton edited and published a newspaper called 'The South Polar Times', to which men would submit articles of a scientific or humorous nature, often written anonymously or under a pseudonym.

Life at camp

In September, at the start of the summer, four preliminary sledge parties were sent out to lay depots for a journey towards the South Pole. However, bad weather forced them to return. A second attempt later in September succeeded in laying a depot of a week's worth of food. By now many of the crew were showing signs of scurvy but this was remedied when one of the sledging parties returned with half a ton of seal meat, which provided some necessary vitamin C.

Sledge parties sent to lay supplied in depots

On 30 October the support party for the Southern Journey – the journey south towards the South Pole – set out.

Support party sets out for main expedition

The main party consisting of Scott, Shackleton and Wilson set out to begin their Southern Journey.

Main party sets out

The main party was unsupported from this time. This became perhaps the most famous of the sledge journeys undertaken by the expedition, despite being beset with problems. On the outward voyage, as Discovery travelled through the Tropics, the dog food had become contaminated in the heat and the dogs would not eat it. This greatly reduced the dogs' capacity to haul the sledges. All the team could do was go as far south as the dogs could manage and then resort to man-hauling their sledges. As the dogs became increasingly weak the sledge loads had to be carried forward in halves. The image shows a group man hauling.

The main party continues the journey unsupported

The first dog died, and was fed to the others. It was decided that the best nine dogs would be saved by feeding them the weaker ones. Wilson took on the job of killing the dogs.

It was not just the dogs that suffered; the men suffered badly from the effects of their trip. Food was strictly rationed and the quantities were too small to provide the necessary energy for man-hauling. Shackleton was the first to show the early signs of scurvy. Snow blindness also affected them, and at one point Wilson suffered so badly he had to haul his sledge blindfolded.

Food supplies and nutrition problems

The men celebrated Christmas Day in their tent finishing with a Christmas pudding that Shackleton had hidden in a sock. On 31 December, having reached the furthest south of 82°16′33′′S, a new southern record, they turned back. On the return journey all three men began showing signs of scurvy. Shackleton, suffering particularly badly, was ordered not to pull the sledge but to walk alongside it. The image shows them, faces badly sunburned, when they returned.

Celebrating Christmas

The group returned to Discovery. On their return they learnt that the relief ship, the Morning, was in an area of water called McMurdo Sound to re-supply Discovery but was still frozen in the ice. They would need to wait until the summer when the ice would melt before they could free the ship and give Discovery the necessary supplies.

Delays to receiving fresh supplies

All except eight of the crew volunteered to spend another winter in the Antarctic. The eight who wished to leave left for Britain. Shackleton was sent home due to his poor health but against his wishes.

Crew changes

Sledging plans were made when the sun returned. The sledging season would be short if Discovery was still icebound at the beginning of Antarctic summer, as they needed to ensure that enough men were available to help free the ship if necessary. The first sledging party left for Cape Crozier to collect penguin chicks. They arrived back safely suffering from nothing more than a little frostbite and bringing with them penguin chicks and eggs. There were two other trips planned – Scott would lead a party west up the Ferrar Glacier, and Barne would lead a party to explore an inlet south of McMurdo Strait.

Preparing for another attempt

Scott, with twelve men, began the journey to explore the area to the west of the base camp. Scott's advance party included Skelton, Thomas Feather, PO Edgar Evans RN, William Lashly RN and Jesse Handsley RN. There was a geology party made up of Ferrar, P.O. Thomas Kennar RN and William Weller, and a support party of F.E. Dailey, Thomas Williamson RN and Frank Plumley RN. However, they were forced to return to camp when the rough terrain damaged the sledge runners.

The main group sets out again

The sledges were fixed and the men set out again within the month. They were badly affected by winds and blizzards but made it to the top of the glacier, 8,900 feet above sea level. Here the party was split into two groups and the advance party of Scott, Lashly and Evans continued to march. By the 30 November 1902, they were forced to turn back due to poor weather conditions.

The main group becomes separated

On their return journey the three men accidentally slid 300 yards down a valley. They were badly bruised, but fortunately no one was injured. When they reached the steep slope, they roped themselves together; Scott and Evans fell into a crevasse, with Lashly left hanging onto a sledge. Scott was able to use his crampons to get a foothold and was able to drag himself to safety, so that Evans could then be hauled upwards and out.

They returned to Discovery to find it still ice bound.

Deadly accidents threaten the group

The relief ships Morning and Terra Nova came into view. They brought with them the unwelcome orders that if Discovery could not be released in time she would have to be abandoned. Dynamite was used to try to blow a channel through the pack ice.

Discovery stuck in the ice

Luckily after five weeks the ice broke up and the ship was eventually freed.

Discovery is free from the ice

On his return to Britain, the Royal Geographical Society awarded Scott the Patron's Gold Medal. He also received an honorary degree of Doctor of Science from the University of Cambridge in recognition of the major scientific advances made by the expedition in the study of the Antarctic.

Recognition of the expeditions many achievements

Nimrod:

11 August 1907After inspection by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, Nimrod sailed on 11 August 1907. Shackleton remained behind on expedition business; he and other expedition members followed later on a faster ship and joined the rest of the crew in New Zealand.

The Nimrod leaving Lyttelton, Jan 1st 1908

When the expedition departed on Nimrod from Lyttelton New Zealand, 30,000 people gathered to wave them off. As transport, Shackleton brought sledges, 9 dogs, 10 ponies, and an Arrol-Johnston motor car.

The expedition had a stormy start with gale-force winds and swells besetting the ship for ten days. One of the ponies became so distressed it had to be shot. All of the men suffered; Shackleton said everyone on board lived in 'constant wetness, wakefulness, and watchfulness.

In order to save on coal Nimrod was towed 1,400 nautical miles from Lyttelton to the ice edge by the steamer Koonya. Once the first icebergs were spotted, the towline was cut and Nimrod carried on unaided.

Nimrod departs from New Zealand

The Ross Ice Shelf was spotted and due to the large number of whales, Shackleton named this area the Bay of Whales.

Shackleton had originally promised Captain Scott that he and his crew would not build their base near the old Discovery Expedition base at Hut Point on Ross Island . However, the sea ice conditions made it unsafe to set up camp and Shackleton had to break his promise. During the preparations to unload Nimrod the second officer Aeneas Mackintosh was hit in the face by a hook and was blinded in one eye. He returned to New Zealand with the ship but did take part in further Antarctic Expeditions.

Shackleton breaks his promise to Scott

Nimrod followed the coast of Ross Island to Cape Royds, 20 miles from Hut Point. Shackleton found an ideal place to camp surrounded by volcanic hills, which sheltered the camp from prevailing winds. There was fresh water nearby and Adelie penguins provided a source of fresh meat. The men unloaded their supplies, built a stable for the ponies and assembled a prefabricated hut. The shore party would consist of 15 men who would spend the winter in the hut. Nimrod then departed for New Zealand, arranging to return for the men in 1909.

A camp is made at Cape Royds

Mawson, Dr Alistair Forbes Mackay, Jameson Adams, Dr Eric Stewart Marshall and Sir Philip Lee Brocklehurst, set out to climb Mount Erebus (3794m), which overlooked the camp on Ross Island. This was the first ascent of one of the world's great active volcanoes. The summit party, David, Mawson and Mackay were the first to reach the top, where they took photographs, meteorological experiments were carried out and rock specimens gathered. Long, steep snow slopes meant they were able to save time by sliding back down. The only casualty of this excursion was Brocklehurst, who had to have a toe amputated due to the effects of frostbite.

Back at the camp four of the ponies had suddenly died. An autopsy on one revealed they had developed a taste for the volcanic sediment; its stomach was filled with sand. This reduced the number of ponies available for the journey south and from then on the men had to watch them carefully.

First ascent of Mt Erebus

During the Antarctic winter the men busied themselves with work: meteorological measurements were recorded twice a day, and experiments to test the limits of microscopic organisms found in melting ice were carried out. In addition, the men wrote, typeset, printed, and bound over 30 copies of the first book ever published in Antarctica – the Aurora Australis.

Having been unable to lay a depot towards the south earlier Shackleton was forced to go on a supply trip to Hut Point with Professor David and Bertram Armytage. It was from there that Shackleton and his team would start the trek to the pole in October 1908.

By mid-October a depot was established at 79°S and the men then returned to the camp.

South Pole depot laying

Three sledging parties were planned for the summer. They were to go in a northern, a western, and a southern direction.

The Northern Party: 5 October 1908 – 4 February 1909

The Northern Party (David, Mawson and Mackay) left the winter quarters on 5 October 1908, where with the help of the motor car they laid depots for their return journey. The plan was to head northwards along the coast of Victoria Land hoping to find a passage to the polar plateau and be the first to make it to the magnetic South Pole and to carry out a full geographical survey of the Dry Valley area.

The Northern Party sets out

They planted the British flag taking possession of Victoria Land for the British Empire. Realising that their provisions would not get them to the magnetic pole and back they decided to reduce their rations and supplement their diet with seal meat. In addition, they used seal blubber to make their paraffin supplies last longer. They discovered that the Magnetic Pole was further south than originally thought.

The Northern Party takes possession of Victoria Land

The Northern party reached the mean position of the magnetic South Pole on 16 January 1909 at 72° 15' S, 155° 16' E, at an elevation of 7,260 feet (2,210 m)

Magnetic South Pole is reached by the Northern Party

Their journey back was troubled with dwindling food supplies. When the Northern Party failed to return, Nimrod began to sail along the coast line looking for them, but it was a very large area with heavy drifting snow and they did not know exactly where the party were.

Nimrod begins a search for the Northern Party

Luckily the Northern party heard Nimrod approaching and emerged from their tent to see it coming into the inlet where they were camped.

In their excitement they rushed to the shore where Mawson fell into a crevasse landing only 60cm above the sea. The others were so weakened by their trek they were unable to lift him out and had to wait for help from the crew of Nimrod. A beam was brought ashore and laid over the crevasse with a rope around it, so that Mawson could finally be rescued.

Northern Party are rescued

The Western Party: 1 December 1908 – Late December 1908

The Western Party, made up of Armytage, Priestley and Brocklehurst ascended the Ferrar Glacier carrying out a geological survey. It had been planned that they would meet the Northern Party (David, Mawson and Mackay) at Butter Point. They waited but the party did not arrive. Instead, the sea ice on which they were camped broke up and they spent several hours adrift before the floe brought them back to the land. They left to lay a depot at Butter Point for the return of the Northern party. Once the depot had been placed they proceeded up the Ferrar Glacier undertaking a geological survey as they went.

Western Party depart

Just after Christmas the Western party began their retreat to Butter Point where they were due to meet up with the Northern Party and be collected by Nimrod. However, neither were there and the party were forced to wait and camp on the sea ice. Unfortunately the ice had broken away and was drifting toward the open sea. The group spent a day on the ice being buffeted by killer whales, before their ice bumped into the a glacier allowing them to trek back to Butter Point. The following morning Nimrod appeared.

Western Party are rescued

The Southern Party: 29 October 1908 – 1 March 1909

The Southern Party led by Shackleton with Frank Wild, Eric Marshall and Jameson Adams set off, their aim being to reach the South Pole. Their supporting party of Brocklehurst, Ernest Joyce, Bertram Armytage, Raymond Priestley and George Marston took the first car to the Antarctic, but it proved useless on soft snow and uneven surfaces. The main party was also finding that the difficult terrain was problematic for the ponies who were meant to be hauling the sledges, and eventually the team had to resort to man-hauling them.

Shackleton cut the party's rations to make the supplies last longer and, as the ponies collapsed, they were shot and their meat used for depot laying and added to rations. Realising they had not brought enough food for the return journey, the men's rations were continually reduced, until they were existing on two biscuits per day in the hope this would stretch out their food enough to make the Pole attainable.

Southern Party sets off

The Southern Party reached the head of the Beardmore Glacier, where they had to relay loads on the sledges. As they climbed higher, the men began to suffer the effects of altitude sickness and the air was so cold that their beards were frozen with the moisture from their breath. At this point Shackleton became concerned for the fate of his men; he realised that whilst the Pole was attainable they would not survive the return journey.

Southern Party reach the polar plateau

Christmas Day was marked with a little more food than usual, and the men celebrated with a hot meal of 'hoosh' made from meat, fat and biscuits; plum pudding with coca and brandy, and a spoonful of crème de menthe. On the horizon they could see what were later named the Transantarctic Mountains that flanked the Ross Ice Shelf.

This image (from left to right) shows Adams, Marshall and Wild – Photographer: Shackleton

The Transantarctic Mountains are discovered

Shackleton decided that the Pole could not be reached without loss of life and they should turn round.

The march to the Pole is abandoned by the Southern Party

The Southern Party walked a few more miles and on 9 January 1909 raised a Union Flag at 88°23′S, just 180km from the South Pole; this was the furthest south that anyone had ventured. Shackleton named the polar plateau after King Edward VII. The party turned for home. Extremely short of food, reaching the depots was all that mattered. At one point they marched for 14 hours on a cup of tea, two biscuits and two spoonfuls of cheese.

The image (from left to right) shows Adams, Wild and Shackleton. Photograph: Marshall

Furthest South and the beginning of the return journey

Struggling back, they reached a depot where they had stored pony meat but it had become contaminated and the party developed dysentery, resulting in a much slower pace. They continued to the remaining depots, at one finding some frozen blood from one of the ponies which was a welcome addition to their rations. They continued marching, sighting Mount Erebus and reaching two further depots. However, the health of the party by this stage of the journey was extremely poor.

Depots are reached

Despite finding plentiful supplies at Bluff Depot, Marshall collapsed with severe dysentery. Shackleton left him with Adams, whilst he and Wild struck out for Hut Point where they hoped that help could still be found, since Shackleton had previously ordered that a small party should overwinter at the hut and that Nimrod should sail north at the end of February.

Marshall collapses

Shackleton and Wild arrived at Hut Point on the 28 February to find plenty of supplies and a note saying the ship would wait in the area until 26 February – they had missed Nimrod by two days.

In the morning Shackleton and Wild set fire to a magnetic observation hut, hoping that Nimrod would be close enough to see the flames. The ship had been returning with a search party and spotted the fire. Once on board, Shackleton was able to guide a rescue party to Marshall and Adams. Shackleton was reunited with the other sledging parties and base camp members he had not seen since his departure on 29 October 1908.

The Southern Party is rescued

The expedition made its way to New Zealand, arriving on the 22 March 1909.

The journey ends

Terra Nova:

1 June 1910The expedition left London on the ship Terra Nova, but it was only when the ship arrived in Melbourne, Australia that Scott learnt of Amundsen's intentions to try for the South Pole. Until this point the world had believed that Amundsen would be making an attempt on the North Pole, but hearing of the independent claims made by the American explorers Frederick Cook and Robert Peary that they had reached the North Pole, Amundsen set his sights on the south. Amundsen's own crew did not know of the change of plan until they reached Madeira.

Expedition leaves London on the ship Terra Nova

Terra Nova sailed from Australia to New Zealand to resupply and to embark the ponies. Scott continued to raise funds for the expedition in Australia and New Zealand and rejoined the ship in Lyttelton, where he said goodbye to his wife Kathleen as the ship sailed for the Antarctic on 29 November.

Terra Nova sets off for the Antarctic

The journey from New Zealand to Antarctica was a difficult one when the Terra Nova ran into a storm and was battered by 55 mph winds. The overloaded ship was forced to throw ten tons of coal and 69 gallons of petrol overboard. The Manchurian ponies suffered particularly badly; even with the constant attention of Captain Oates two of them died during the storm. The dogs also suffered and fighting broke out between them as the ship lurched from side to side; one dog died during the storm. The ship itself was in a bad way with the main pump clogged and the hand pump failing. Water rose and the furnace fires were put out causing the engines to stop. Engineers up to their necks in water finally unclogged the pumps. The ship was then delayed for three weeks by pack ice, which was encountered much further north than had been expected.

Finally emerges from ice

On arrival at Ross island, the ship had to be unloaded. Without much previous training, the dogs proved difficult to handle and it took time to get them used to hauling supplies. Even worse, one of the motorised sledges fell through the ice and was lost.

The party worked to build a hut to winter in, measuring 50 x 25 feet. It was insulated with seaweed mats and contained a stove and cooking range, sleeping quarters and laboratories. A partition was made between the men and the officers' quarters by stacking supply crates to make an interior wall. When not working, the men relaxed by playing football and attending a variety of talks and lectures. The expedition's photographer Herbert Ponting would entertain the men with images from his travels around the world. Ponting also built himself a darkroom inside the hut, where he could develop his photographs. 'The South Polar Times', the expedition newspaper set up by Shackleton on Scott's Discovery Expedition 1901-04, was revived and the men were encouraged to submit articles of a serious or humorous nature.

During the austral summer the men started laying depots for the journey south, as well as undertaking geological surveys of King Edward VII Land and an investigation of a region west of McMurdo Sound. This gave the men time to test out their various transport methods. They found that the motorised sledges often broke down in the extreme cold. Concerns also developed about the ponies as they were struggling with the cold and deep snow. Scott led a team of 12 men to lay One Ton Depot. He was hoping to establish this at 80°S, but conditions forced the team to lay the depot 30 miles short of this goal.

Men unload the ship

Returning from an expedition along the coast, Terra Nova sailed into the Bay of Whales to find a ship anchored to the ice, which the crew recognized as the Norwegian's ship Fram. Campbell, Levick and Pennell had breakfast with the Norwegians on Fram and Amundsen, with two companions, had lunch on board Terra Nova. Amundsen reported that his attempt for the Pole would not take place until the following Antarctic summer.

Terra Nova meets Fram

The members of the Northern Party undertaking a geological expedition were to be picked up by Terra Nova on 18 February from Evans Cove, but the ship could not reach them through the heavy pack ice and the rescue attempt was abandoned, leaving six men to overwinter with very few supplies in a small ice cave.

Northern Party marooned

The first Antarctic winter sledging trip left Cape Evans on 27 June 1911 with, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, Henry Bowers and Edward Wilson setting out for Cape Crozier. Their journey intentionally took place in winter so that they could observe the Emperor penguins wintering and collect their eggs for observation. This was an incredibly tough journey; at one point the men were left exposed when a blizzard blew their tent away. Luckily, they were able to locate their tent the following day – had they not managed this they would almost certainly have died.

The first Antarctic winter sledging trip begins

When the men returned to Cape Evans they were exhausted and their frozen clothes had to be cut off their bodies. However, three of the eggs were still intact. Cherry-Garrard would later write the book 'The Worst Journey in the World' telling of the hardships of their expedition.

Sledging trip returns from 'the worst journey in the world'

The major sledging trip of the expedition was led by Scott in an attempt to be the first to reach the South Pole. This journey began with three types of transport: the motorised sledges, a team of dogs, and a team of ponies all being used to bring supplies across the Ross Ice Shelf. The motorised sledges were useful to begin with but broke down and both were abandoned by the beginning of November.

Attempt on the South Pole begins

The ponies did not fare as well as had been hoped; they struggled with the low temperatures, high winds, lack of water and soft snow. Captain Oates determined efforts with the ponies meant that they achieved the task of hauling supplies.

First pony shot

At the foot of the Beardmore Glacier the final ponies were shot and at 'Shambles Camp' a depot containing pony meat was set up.

Remaining ponies shot

The dogs returned to Cape Evans and Scott and the rest of the men continued up the Beardmore Glacier, now man-hauling the sledges. Osman, Scott's dog was leader of the sledge dogs, and Scott admired him for his brave and determined character.

Man hauling of sledges begins

Scott chose Wilson, Oates, Evans and Bowers to join him on the final push for the Pole. The decision to have five men instead of four in the Polar Party seems to have been made at this late stage and Bowers had to repack the sledges to take account of the extra rations needed. Parts of their journey across the Polar Plateau were slow as they encountered sastrugi (hard ridges of ice and snow), which made travel on skis difficult.

Scott chooses the South Pole party

Bowers, who had very keen eyesight, spotted a black dot on the horizon. Knowing this could not be natural, the men began to suspect that the Norwegians had already made it to the Pole.

First evidence they may not be first to the South Pole

When they arrived at the Pole, their worst fears were confirmed. The Norwegians had made it 35 days earlier and Amundsen had left a tent containing a note for Scott, asking him to deliver a letter to the King of Norway, in case the Norwegian team failed to get home. Scott wrote in his diary 'Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward for priority.' They raised the Union Jack and took a number of photographs.

Arrival at South Pole after Amundsen

Glass plate negative

Glass plate negative;The Pole Party on the Trail. Print from film neg

The trek home began. At first they made good progress but slowly the effects of the cold and scurvy set in. They reached the upper Beardmore depot; from here they had a five day march with just enough rations to reach the next depot – there was no margin for error. The weather was good and they stopped to collect 35 pounds of geological specimens. This was in line with the scientific motives of their expedition. They only just made it to the next depot and by this point Evans was steadily declining.

Setting off to return home from South Pole

Evans took a turn for the worse when he fell into a crevasse along with Scott. It is thought that Evans hit his head and suffered a concussion, Scott describes him as being 'broken down in the brain'. He may also have been suffering from blood poisoning, as he had cut his hand on a sledge runner earlier on the journey.

Evans falls and suffers concussion (damage to brain)

Evans stopped to tie his boots. When he did not catch up with the others, they skied back to find him. He was found in a confused state on his hands and knees in the snow and he was put on the sledge and hauled back to the tent. Evans died at 12:30 am.

Leaving Evans' body behind, the men trudged on, reaching the Shambles depot. Here there was a supply of pony meat and the men could have a satisfying meal. They then continued onto the next depot, but discovered that the fuel had leaked as the leather washers on the fuel cans had shrunk in the cold and the some of the fuel had evaporated. On reaching the next depot the situation was similar, but here they were short of both fuel and food. Oates was struggling very badly from the effects of frostbite. Eventually his sleeping bag had to be cut just to enable him to get in.

Evans falls and suffers concussion (damage to brain)

The effects of frostbite severely restricted Oates' speed, and he asked to be left behind. The men refused, but on the morning of his 32nd birthday, Oates told his companions, 'I am just going outside and I may be some time.' He left the tent and walked out into a blizzard, never to be seen again. He gave his life in the hope that the rest of the party would be able to move faster without him.

Oates dies

Expecting to meet the returning Polar Party, Cherry-Garrard and Demetri arrived at One Ton Depot, waited for a week and then returned to Cape Evans. They had not proceeded further south as Scott had planned.

Support team return to camp

Eleven miles from One Ton Depot the three remaining men, Scott, Wilson and Bowers, made their final camp, where a severe blizzard prevented them from leaving their tent. They only had enough food for a couple of days and fuel for one hot meal. Trapped in their tent, the men wrote their farewell letters to family and friends. Scott also wrote his 'Message to the Public' which outlined his reasons for the disaster that had befallen him and his men. It is thought that Scott was the last of the three to perish and his last thoughts were of the families of his men – the last words in his diary were 'For God's sake look after our people.'

Trapped in their tent 11 miles from One Ton Depot

By the time that Cherry-Garrard and Demetri's support party returned to Cape Evans, it was clear to the surviving members of the expedition that Scott and his party had certainly perished.

Acceptance that Scott, Wilson and Bowers have died

A search party under Commander Atkinson RN set out to rescue the missing Northern Party, but were beaten back by the weather.

Search party sets off to relieve Northern Party

After their ordeal overwintering on Inexpressible Island, the Northern Party walked the 230 mile journey back to Cape Evans, arriving on 7 November 1912.

Northern Party returns

The bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers were found on 12 November 1912 inside their tent. The search party collected their personal items, journals and letters and then collapsed the tent over the bodies. A cairn was erected over the tent and a pair of skis used to make a cross. They searched for Oates' body but were unable to find it and so erected a cairn in his memory. The search party brought back with them the geological specimens which Wilson had insisted they haul back even when the Polar Party were exhausted. These specimens have been extremely useful in establishing the geological history of Antarctica.

Bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers found

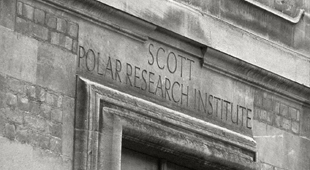

When the Terra Nova returned with the news that Southern Party had perished there was a worldwide outpouring of sorrow. A memorial fund was set up which raised money to pay the men's widows and clear the debts of the expedition. Enough money was raised to found an institute in Scott's memory; this was the Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) at the University of Cambridge, which still carries out polar research today.

The Scott Memorial fund is established and the Scott Polar Research Institute is created

Endurance:

8 August 1914The ship Endurance left Britain sailing towards the Weddell Sea via South Georgia (They also stopped at Madeira, Montevideo and Buenos Aires). The expedition found much more heavy pack ice than they were expecting. They steamed along the ice barrier for a few days, discovering and naming the Caird Coast. They made very slow progress through the pack ice.

Expedition begins

At 76°34′S Endurance became frozen into the ice which had closed in around the ship during the night. As far as the eye could see there was ice and nothing the men tried would free the ship.

Whilst stuck in the ice, the men lived comfortably on the ship but they knew that eventually they would need to leave as the pressure from the ice was slowly crushing it. Hurley, the ship's photographer, took a series of photographs that depict the damage caused by the ice on Endurance.

Endurance becomes frozen in ice

By the 18th of October, Endurance had a 30–degree lean.

The ice lifts Endurance and pushes it sideways

The ship was damaged beyond all hope when her stern was crushed by the ice. On 27 October, Shackleton gave orders for the men to abandon ship. They took three life boats, sledges, and approximately a month's supply of food; the rest was inaccessible amongst broken timbers in the hull. A camp was established on the ice floe, but this was to be temporary due to its instability. All ambitions of crossing Antarctica vanished as Shackleton now planned how to get his men home safely.

Endurance is damaged beyond repair and abandoned

The next day, the men were instructed to get together no more than two pounds of essential personal gear and pack this onto the sledges. Hurley returned to the ship and rescued 400 of his glass plate negatives showing images of the expedition, but as he could carry no more than 150 he was forced to select the best ones. To make sure he would not be tempted to go back to the sinking ship to collect any more, Shackleton ordered Hurley to smash the rest of his glass plates.

Vital supplies and a small selection of photographs are removed from the doomed ship.

Ocean Camp was established on the ice floe. A camp routine was organised with each man having a job to do so that no one could get bored or despondent.

New camp established on the ice

Shackleton looked towards the shattered remains of the Endurance and announced 'She's going boys'.

Endurance finally sinks

The men had taken three small boats with them from Endurance, the James Caird, the Dudley Docker, and the Stancomb Wills, named after three of the expedition's sponsors. These were put on sledges and dragged northwards across the sea ice in relays. There was a fear the boats would be damaged, so they moved to the strongest floe they could find and set up Patience Camp.

The ice floe on which they were camped broke away from the pack ice and began to shrink as it floated into warmer waters. Shackleton ordered that the boats be packed and ready to go at a moment's notice should the ice crack.

The ice starts to break up – life boats are prepared

The men piled into the three boats and set off into the Weddell Sea, hoping to find land.

Boats are launched

After a difficult journey the men reached Elephant Island.

They were overjoyed to be on firm land, rather than on the precarious ice floe. Whilst this was a more comfortable camp they still had no means of communicating with the outside world and their chance of discovery on the island was remote. Shackleton also felt that many of the men were too ill to continue on such an arduous journey. Their best chance of raising the alarm would be to reach one of the whaling stations on the island of South Georgia. However, this was 800 miles away across some of the stormiest ocean in the world. Shackleton decided that he and a small crew would take one of the boats and sail to South Georgia. As they rested for a while, recovering from their journey to the island, the James Caird was modified to make the 800 mile trip. Sledge runners, crate lids and the cook's canvas windscreen were used to build a cover for the boat.

Journey to Elephant Island

Shackleton selected his crew and he, Worsley, McNish, Vincent, Crean and McCarthy set sail on 24 April 1916. They spent the journey divided into two watches: four hours on, four hours off. The men suffered terribly from seasickness, and were wet, cold and exhausted for the entire journey. On the three occasions they saw the sun Worsley had to be held steady by two men so that he could read the sextant to position them. At one point the boat was almost overwhelmed by a huge wave and all hands had to set to bailing water; for ten minutes they did not know if it would be possible to save the vessel.

Rescue party sets off to get help

The James Caird reached South Georgia during a storm and the men had to struggle to prevent the boat from being driven onto the rocks overnight. Unfortunately, they had arrived on the opposite side of the island from the whaling station. Their best chance of reaching safety was to walk across the mountainous interior rather than putting their boat to sea again. However, the interior of the island had never been traversed and was assumed to be impassable. The men rested in a cave and ate albatrosses and seals which they managed to catch.

Arriving in South Georgia

When they were a little recovered, Shackleton, Worsley and Crean set off to get help at the other side of the island, leaving the other three men as they were too weak to travel further. The distance was approximately 17 miles, as a bird would fly, but the terrain was very difficult. They set off at 2am and walked for 36 hours across the Allardyce mountain range.

Trekking over the mountains to safety

Shackleton, Worsley and Crean arrived at the whaling station at Stromness after a 36 hour trek. Their shaggy, worn appearance amazed the whalers – they were hardly recognisable as human.

The Norwegian whaling manager was aghast at their condition and gave the men food and beds, and arranged for the rescue of the men on the other side of the island. Worsley accompanied the rescue ship; in his clean shaven state he was unrecognisable to Vincent, McNeish, and McCarthy, with whom he had spent the last eighteen months.

Rescue

Shackleton discovered not only that the war which had been imminent on their departure was still going on, but that his other party, the Ross Sea Party, had also run into trouble. Aurora had broken away from its winter quarters before all the stores could be unloaded. After a long period adrift the ship safely reached New Zealand; however, the fate of the shore party was unknown. Shackleton needed to arrange two rescue trips, one for the Weddell Sea party still on Elephant Island and another for the party stranded on the Ross Sea coast.

Shackleton arranged the rescue of his men trapped on Elephant Island. Under the charge of Frank Wild, they had managed to construct an improvised hut, using two upturned boats, some stones and a canvas. This created some shelter for the men, where they lived for 138 days eating penguin and seal meat. Each morning Wild would order 'Lash up and stow boys, the Boss [Shackleton] may come today'.

Setting off to rescue the crew from Elephant Island

After three failed attempts, Shackleton did reach his men in the Chilean steamer Yelcho. When the ship was spotted a fire was lit on Elephant Island to attract its attention and allow the Yelcho to pinpoint exactly where the men were. All the men were well and all had survived; they were on board within the hour.

Rescued at last from Elephant Island

Shackleton then turned his attention to rescuing the other party of the expedition, stranded at the Ross Sea. The Aurora had been blown out to sea and was imprisoned in the ice for a year before being towed to New Zealand.

Despite many hardships the men of the Ross Sea party had managed to carry out their role in the expedition and had laid the sledging depots for the expected crossing party.

Aurora left New Zealand with Shackleton on board as a supernumerary officer to rescue the men, reaching McMurdo Sound on 9 February 1917. Of the ten members who had been stranded, three had died, including the leader Captain Aeneas Mackintosh. The ship arrived in New Zealand, bringing all the remaining members of the expedition to safety.

Many of the men of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition went on to serve in the First World War, including Shackleton who was sent to South America and then to Northern Russia in charge of Arctic equipment and transport.

After the expedition

British Graham Land:

10 September 1934Some expedition team members left Britain on-board the expedition's vessel Penola.

Expedition leaves Britain

In the Falkland Islands, Penola made rendezvous with the BGLE's members who had sailed south with the plane and dogs abroad freighters.

Additional dogs from Labrador were sent south after many of the original dogs from Greenland died from canine distemper, a viral disease. En route, Edward Bingham, Wilfred Hampton, the plane and dogs were all transferred to Discovery II, sailing ahead of Penola to the British Antarctic base at Port Lockroy.

Rendezvous with the full expedition team

After leaving the Falkland Islands, an inspection of the Penola revealed that the timbers on which the engines were placed had warped while travelling through the tropics. Despite repairs, the engines began to move about on their mounts. The ship returned to collect concrete on which a solid mount could be made for the engines and then set a course for Antarctica under sail. Penola finally reached Port Lockroy on 22 January 1935

Ship repairs required

The plane flew south with Hampton at the controls, and Rymill and Robert Edward Dudley (RED) Ryder – Captain of the Penola – on board,seeking a site for the Northern Base. They saw several possibilities for a location among the Argentine Islands. Returning aboard Stella, Quintin Riley's motor launch, they chose 'Winter Island' with its sheltered mooring, as a suitable area for the hut. A prefabricated two-storey building was swiftly erected. This included a hangar within which the plane could be stored with its wings folded.

The building included a two-storey area containing a kitchen, workshop and wireless area downstairs, with sleeping and living quarters above.

Flights begin to locate a site for the northern base

The hut was completed, and the men hunted seals and collected penguin eggs to supply them through the winter.

Food is gathered for the winter

The BGLE team celebrated the Antarctic Midwinter with good company, fine food, excellent drink and enthusiastic singing.

Antarctic Midwinter celebrated

In their first year the sledging season was short as treacherous sea ice conditions prevented any major sledging journeys farther south. Instead, a detailed survey of the area between the Argentine Islands and Cape Evenson was undertaken.

Winter activities and achievements

Penola sailed north to collect timber from Deception Island for a new base farther south.

Timber for the base is collected

The entire expedition moved south to the Debenham Islands in Marguerite Bay. These five islands were named after the children of Professor Frank Debenham, the then Director of the Scott Polar Research Institute and Assistant Geologist on Captain Robert Falcon Scott's 1910-13 Terra Nova Antarctic expedition . Barry Island was chosen as the site for a hangar and single storey building and preparations for major sledging journeys began.

Change of expedition base location

Penola sailed north to the Falkland Islands, with a minimal crew. Once there, the ornithologist Brian Birley Roberts had to have an emergency operation to remove his appendix. The ship then sailed on to South Georgia where a floating dock was available for repairs. An inspection of the propeller shafts revealed that they had worn so badly that they were in jeopardy of snapping. If this had happened, water would have poured in and sunk the ship.

Essential repairs required on Penola

The rest of the party remained to winter in the Antarctic. Several journeys were undertaken by dog sledge. The longest, lasting 10 weeks, explored the coast 340 miles south of the Southern Base at Marguerite Bay.

The sledges were pulled by dogs; however, they found the going difficult due to soft snow and often had to relay their loads in halves.

At other times one of the group would walk ahead, testing the ground with a 3-metre whip; if the whip failed to hit solid ground they would try somewhere else and alter the course accordingly.

Winter in the Antarctic

A major effort was undertaken to sledge south, across the sea ice, and lay depots for the coming summer. A storm broke up the sea ice around the sledge parties. After hours of navigating breaks in the ice and sea ice being swept into large obstacles, they clambered onto a group of islands, naming them Terra Firma. Abandoning the depot-laying plan, two survey groups moved north, concentrating on the Laubeuf Fjord region, and the channel between Adelaide Island and the mainland.

Sledging south across the sea ice

The major southern sledge journeys commenced. The initial snow and ice conditions were so difficult that Rymill and Bingham transferred their supplies to expedition members Alfred Stephenson, Reverend (William) Launcelot Scott Fleming and (George) Colin Lawder Bertram [Note: William and George were their first names but they were know by Launcelot and Colin] allowing them to keep moving south while Rymill and Bingham returned to Base for new supplies.

Stephenson, Fleming and Bertram sledged south along King George VI Sound (now 'King George Sound') as far as 72ºS. From here they were able to map to 72º 30'S, but were unable to ascertain how much farther south the Sound continued. On their return journey they landed twice on Alexander Land (now 'Alexander Island') where Fleming collected rocks and fossils at Fossil Bluff and Ablation Camp.

En-route south, Rymill and Bingham met the returning party from the Sound and were informed that neither the Sound nor Alexander I Land could provide a route to the Bellingshausen Sea, as had been hoped. Rymill and Bingham then went east across Graham Land in the hope of reaching the Weddell Sea. They observed 'about 50 miles of coast' but could not reach the sea due to ice cliffs and glaciers.

Expedition discoveries

The sledge parties were reunited at Southern Base. Despite the challenges, the expedition had been a success and many lifelong friendships were formed.

Return to base

Penola arrived to collect the wintering men. They left for South Georgia from which most of the shore party returned to the United Kingdom on board the Coronda, a whaling transport vessel. On the 4 August 1937, Penola arrived back in the United Kingdom. The members of the BGLE were awarded the Polar Medal, or a clasp if they had already received the medal for other expeditions.