British Graham Land Expedition 1934-37

Expedition Aim

To undertake exploration, scientific research and to assess the economic potential of the Antarctic Peninsula. The British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE) had three major goals:

- Reassert British territorial claims in Antarctica,

- Explore along the west coast of Graham Land and find channels that led to the Weddell Sea (using these as a route to explore the west coast of the Weddell Sea)

- Undertake scientific research for academic and commercial purposes.

Summary

- The British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE), 1934-37, was undertaken by sixteen keen, young explorers, scientists and military officers. Led by an Australian, John Rymill, the expedition's aims were to reassert British claims to the British Antarctic Territory, as well as to undertake exploration, scientific research and to assess the economic potential of the area.

- Despite modest financial resources, treacherous sea ice and difficult terrain, the BGLE was a great success. The expedition solved a geographical mystery, collected significant scientific data and established the foundation of Britain's ongoing scientific endeavours in Antarctica.

- An Antarctic expedition had originally been planned by Gino Watkins, who had died on an expedition to the Arctic. Rymill put together a team to investigate Graham Land, which was one of the least well known areas of the British Antarctic territorial claim.

- 16 men, led by Rymill, left Britain on board the sailing ship Penola, with the research vessel Discovery II also transporting their supplies, including dogs and two aircraft.

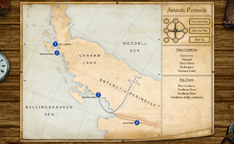

- Sledging journeys were carried out between September 1936 and January 1937. They made many significant findings, discovering that Graham Land was not an island, as previously thought, but was a peninsula.

- The expedition surveyed and mapped the Graham Land coastline and undertook zoological and geological observations.

Background to the expedition

In 1931, Arctic explorer Gino Watkins (1907-32) proposed an expedition to cross the Antarctic continent, if funds permitted, or a smaller expedition to undertake exploration and scientific research in British Graham Land. Unable to raise the necessary support and funds, he subsequently returned to Greenland to continue the work of the British Arctic Air Route Expedition (BAARE), 1930-31. Whilst out hunting for food during the East Greenland Expedition (1932) he disappeared. Only his kayak and some clothing were found. John Rymill led the expedition after Watkins's death. On his return to Britain, Rymill began the preparations for an expedition to explore Graham Land.

Rymill developed Watkins' idea for an expedition to Graham Land into a plan that was endorsed by the Scott Polar Research Institute, the Royal Geographical Society and the Colonial Office. When the British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE) was planned in 1933, Graham Land was believed to be the largest of a group of islands lying to the North-West of the Antarctic mainland and separated from it by three channels, the main one being the Stefansson Strait. Graham Land was one of the least well known sectors of the British Antarctic territories.

Funds were provided by the Royal Geographical Society (£1,000) and the Colonial Office (an initial grant of £10,000), as well as individual sponsors. Various goods were also donated. Despite this official endorsement and support, the BGLE took place during the Great Depression and was desperately short of funds. Whilst a small number of the

Background to the expedition

expedition were seconded from the military and paid, the majority of the expedition's sixteen members were unpaid volunteers, although only a few of the expedition had sailing experience. The Royal Geographical Society, and all three armed services - Royal Navy, Army and Royal Air Force - loaned scientific, navigation, photographic and surveying equipment to the BGLE.

The budget for the expedition enabled them to buy the boat and an aeroplane but was not enough to pay for a crew. Penola was the main transportation for the members of the expedition, with the aircraft, dogs and stores brought south separately.

A de Havilland Fox Moth biplane, equipped with skis and floats, was obtained for aerial photography, checking routes for the ship and dog sledges, and transporting supplies. With floats attached, the plane could fly for 5 ¼ hours and, in still air, travel approximately 450 miles. With skis attached that range could be doubled. The aeroplane was used extensively for reconnaissance (flying over areas to see what they are like.)

The expedition team was led by John Rymill, who also acted as surveyor and second pilot. In addition to a ship's crew of seven, the shore party of 9 included several Cambridge graduates, some of whom had already acquired experience of polar conditions in Greenland on expeditions with Watkins and Rymill.

Awards from the expedition

Their surveying made some significant discoveries; for example, Alexander I Land was shown to be longer than first thought, at over 150 miles in length.

Their major discovery was to disprove a theory made by Ellsworth and Wilkins which claimed that whilst undertaking aerial flights they had seen channels between the Bellinghausen and Weddell Seas, making Graham Land an island or an archipelago (group of islands). However, surveying this area on foot proved that such channels do not exist and that Graham Land is one landmass and part of the Antarctic continent and, therefore, is a peninsula.

This demonstrated that flights over an area are not sufficient to tell the lie of the land and that land excursions were necessary in order to back up aerial surveying.

Alongside this discovery the members of the expedition were also responsible for the mapping of the Graham Land coastline, and various scientific experiments and zoological and geological advances.

The BGLE was highly commended for the quality of its meteorological and survey work. B.B. Robert's and Bertram's field work provided research material for their doctorates. Lancelot Fleming's duties as an ordained minister prevented his writing up the geological aspects of the expedition, but they were carefully catalogued for future researchers.

From the aerial observations made by Hubert Wilkins and Lincoln Ellsworth, it was thought that major channels existed across Graham Land. Rymill was adamant that aerial observations had to be confirmed by observations at ground level. As the BGLE moved further south it was clear that the channels did not exist. In 1934, they had believed that they were travelling to the Graham Land archipelago. In 1937, they returned from the Antarctic Peninsula.

The members of the British Graham Land Expedition were awarded the Polar Medal, silver clasp, with the clasp 'ANTARCTIC 1935-37', and several of them had the honour of addressing the Royal Geographical Society.

Life after the expedition

During World War II, the members of the BGLE served in a variety of roles. Rymill joined the Royal Australian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RANVR) before returning to the family farm, also called Penola. Commander R.E.D. Ryder RN was awarded the VC for his leadership of the Operation Chariot raid on the St Nazaire dry dock. In 1940, Lieutenant J.H. Martin RNVR, who served for a time with R.E.D. Ryder, was lost at sea. Major L.C.D. Ryder and his men held back a section of the German advance on Dunkirk, providing extra time for the evacuation on the beaches, until their ammunition ran out. Upon surrendering, he and his men were shot by the Waffen-SS at the Le Paradis massacre.

The Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) supported the war effort by providing information and expertise on the Polar Regions and how to operate these extreme environments. Bertram and Roberts, drawing heavily from their experience on the BGLE, wrote the military Handbook on Clothing and Equipment Required in Cold Climates - 1941.

At the end of the war, Riley and Roberts, who had both undertaken intelligence work during the war, visited Germany to oversee the relocation of German polar and hydrographical records and to establish contacts with polar specialists. Roberts served in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office as a polar expert and was involved in formulating the Antarctic Treaty (1959), as well as the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctica Seals (1972). Roberts was also a part-time Research Fellow at SPRI.

The Right Reverend Launcelot Fleming served as a Royal Navy Chaplain during the war and was director of the Scott Polar Research Institute from 1946 to 1949. In 1959, he was enthroned as Bishop of Norwich and retained a keen interest in rowing at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. In 1971, he became the Dean of Windsor and domestic Chaplain to the Royal Family. In the House of Lords he sponsored a bill for British ratification of the Antarctic Treaty.

Bertram developed cold weather clothing for the military at the beginning of the war, and was Chief Fisheries Officer for Palestine (1940-44). He served as director of the Scott Polar Research Institute from 1949 to 56, and was a Fellow of St John's College, Cambridge.

In 1945, Bingham was appointed Commander of the newly established Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS), the forerunner of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). Within eighteen months he had equipped FIDS and transferred his skills to a new generation of polar explorers and scientists. Bingham was one of an elite group awarded three clasps to their Polar Medal.

Carse served in the Royal Navy during the war. Afterwards, he undertook six expeditions to South Georgia (1951-57), with four as leader of the South Georgia Survey. Carse also worked at the BBC for over four decades. His most famous role was 'Dick Barton, Special Agent'.

Other members of the BGLE made significant contributions in their professional lives. Many of their descendants have travelled south as artists, scholars, scientists and advocates for Antarctica as a continent of peace and science.